Commentaries (some of them cheeky or provocative) on economic topics by Ralph Musgrave. This site is dedicated to Abba Lerner. I disagree with several claims made by Lerner, and made by his intellectual descendants, that is advocates of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). But I regard MMT on balance as being a breath of fresh air for economics.

Tuesday, 29 August 2017

Martin Sandbu advocates nationalising the money supply in the Financial Times.

That’s in this article.

Nationalising the money supply, i.e. stopping private banks from creating / printing money is an idea that has been around for some time. It was advocated for example by Irving Fisher in the 1930s and has been advocated by at least four Nobel laureate economists including Milton Friedman. Plus Positive Money in the UK, Monetative in Germany and various other organisations around the world advocate the idea.

It’s good the see an article in the FT advocating the idea.

Unfortunately Sandbu’s article contains a slight error: where he says “If private management of the money supply is a recipe for instability, the radical alternative is to nationalise the money supply. This is do-able today: central banks can offer accounts to all members of the public (or make central bank reserves available to everyone).”

That implies that it’s the fact of making central bank accounts available to all that results in the state being the monopoly creator of money. One flaw there is that in the UK, to all intents and purposes, central bank accounts have been available to all via National Savings and Investments for decades. But that clearly has not resulted in the state being the monopoly supplier of money.

NSI invests only in base money (i.e. central bank money) and government debt. But government debt, as Martin Wolf explained, is virtually the same thing as base money. So NSI is essentially the Bank of England’s agent set up for the purpose of letting anyone open an account at the central bank (i.e. the BoE). And doubtless some other countries have state run savings banks similar to NSI.

In contrast to Sandbu’s suggestion, what blocks private money creation is insisting that loans by private banks are funded just via equity or similar (e.g. bonds that can be bailed in). Certainly Milton Friedman and Lawrence Kotlikoff, both of who advocate banning privately created money argued for that “fund only via equity” arrangement.

Also, and again contrary to Sandbu’s suggestion, the fact of NOT ALLOWING accounts at the central bank for all does not stop the state being the monopoly creator of money. Reason is that it would be perfectly feasible to have an arrangement where private banks act as AGENTS for the central bank when it comes to the laborous task of opening accounts for tens of millions of people. In fact Positive Money considers that arrangement in its literature.

Indeed, and quite apart from NSI, that arrangement is already up and running in the sense that the proportion of the money supply that is state created is now much larger than ten years ago, but NSI has not expanded in proportion. So how do you me and everyone with a positive bank balance access the expanded proportion of our personal “money supply” which is now central bank created money? Well what is actually happening is that commercial banks act as agents or “go betweens” between ordinary depositors and the central bank.

To illustrate, say you sold Gilts worth £X to the BoE, you’d have got a cheque (or the electronic equivalent) from the BoE for £X. You’d have deposited that at your commercial bank, which in turn would have demanded the BoE credited the commercial bank’s account at the BoE to the tune of £X. Hey presto, you’d have £X at the BoE with your commercial bank acting as agent for the purposes of accessing and transferring that money should you so wish.

To summarise: nice to see a Financial Times article advocating nationalisation of the money supply.

Monday, 28 August 2017

A similarity between NAIRU bashers and anti-racists.

NAIRU (Non Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment) is basically the entirely reasonable idea that there is a relationship between inflation and unemployment and in particular that given increasing demand, the point will come (roughly at the 5% unemployment level) at which further increases in demand, instead of bring more employment, will instead simply stoke inflation.

That’s an idea which is widely accepted in economics and in central bank circles. However, there is a vociferous bunch of people who object to NAIRU because it appears to make a finite amount of unemployment inevitable, and unemployment is wicked and evil. Ergo, so the argument runs, NAIRU must be wicked and evil, i.e. there can’t possibly be a relationship between inflation and unemployment.

As you may have noticed, that makes about as much sense as arguing that cancer causes death, ergo the whole cancer concept is wicked and evil.

Strangely enough, and even more hilarious, one of the main opponents of NAIRU is Bill Mitchell. But Bill cannot escape the fact that there is indeed a relationship between inflation and unemployment very much along the lines of NAIRU. So he gets round that by giving NAIRU a different name: he calls it the Inflation Barrier.

Racism.

A similar form of false logic is popular with anti-racists. Racism is defined in dictionaries as something like the idea that some races are better than others, and/or hatred based on the latter idea. Hatred is obviously wrong. No argument about that. Though on about 99.99% of the occasions when some pompous leftie attributes hate to someone else or some group, there is not so much as the beginnings of an attempt to substantiate the “hate” accusation (which is not surprising, given that proving MOTIVE is not easy).

In contrast, and as regards the simple idea that some races are better than others, at least in some respects, that is a not unreasonable proposition. For example some psychologists claim there are IQ differences between different races. And some races can quite clearly run faster than others. Jews have got about twenty times as many Nobel prizes per head of population compared to Arabs and so on.

However, the whole idea that some races are better than others in some respect other is a bit uncomfortable: it’s at variance with the idea that “all people are equal” – quite obviously true in a sense.

However, reconciling those two apparently conflicting ideas is too difficult for the tiny minds that make up the anti-racist brigade. So they opt for the simpler “NAIRU / cancer” style logic, namely that if something is unpleasant on the face of it, then it can’t possibly be true. And you’re wicked and evil if you suggest it is true.

Sunday, 27 August 2017

Saturday, 26 August 2017

Principles of money.

Summary.

Everyone is entitled to a totally safe bank account at which to lodge money and to have that account underwritten by government. In contrast, they are NOT entitled to let that money be loaned on with a view to earning interest and still expect government to back them. Loans are a commercial transaction and it is not a normal job of government to rescue those who enter commerce and make mistakes. Ergo deposit insurance in the normal sense of the phrase is not justified. That argument actually backs the case for full reserve banking.

__________

James Tobin devoted about 6,000 words to discussing whether deposit insurance was desirable in an article entitled “The case for preserving regulatory distinctions”. The paragraphs below are my stab at the same question (about 1,000 words). Needless to say I think my arguments and conclusion are clearer and more concise than Tobin’s – why else would have written this article?…:-)

1. Everyone is entitled to some sort of depository or bank where they can store money in a totally safe manner. Apart from individual people, many employers find that service of use.

2. That service costs a finite amount, and there is no reason people and employers should not pay for that service, in the same way as people and employers normally pay for the other goods and services they consume.

3. As distinct from storing money in a totally safe fashion, there is lending on money, or letting your depository / bank lend on your money. The fact of lending on, or allowing your money to be loaned out is to enter the world of commerce. Taxpayers do not normally rescue those who make commercial mistakes, and there is no reason taxpayers should have to rescue those make mistakes when it comes to making loans.

4. There are various plausible but flawed arguments in favor of trying to make loaned out money totally safe. One is that money which is not loaned out appears to be a waste of resources. Therefor, so the argument goes, some people who do not lend out their money because of the risks involved should be encouraged to do so by offering them government run deposit insurance, e.g. along the lines of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in the US.

As regards “waste of resources”, that argument is flawed because the large majority of money is simply a book-keeping entry which is generally accepted in payment for goods and service. But a book-keeping entry is not of itself a real resource. In contrast, and to illustrate, a house is a real resource, which if left empty for too long can certainly be argued to be a waste of real resources.

In addition to “book-keeping entry” money, there is paper money (£10 notes for example). But the same applies there as in the case of book-keeping entry money: the cost of creating that money is negligible, thus if large amounts of it are stored, e.g. under matresses, rather than being in circulation, that is not a waste of real resources. Or as Milton Friedman put it, "It need cost society essentially nothing in real resources to provide the individual with the current services of an additional dollar in cash balances."

5. As regards the above mentioned government insurance for deposits which are loaned out, one flaw in that idea is that it is perfectly possible to obtain PRIVATE insurance for deposits, just as private insurance can be obtained for cars, houses, ships and so on. Governments do not normally offer insurance for cars, houses or ships, so why should they offer insurance for deposits?

One answer might seem to be that only the state has a big enough pocket to deal with a large series of failures by depositories / banks. But the state only has that ability because it has COERCIVE powers, e.g. the power to grab extremely large amounts of money by force off taxpayers. Government also has the power to print money in limitless amounts, which may lead to excess inflation which in turn amounts to robbing existing holders of money. Coercion again.

Thus if there is to be free and fair competition between banks and non-bank corporations and firms, i.e. a genuine free market, there is no excuse for the state giving banks and depositors the latter favourable treatment.

6. A classic illustration of the misallocation of resources that results from government run deposit insurance occurred in the 2008 bank crisis and subsequent recession.

That crisis stemmed from excessive and irresponsible lending. Irresponsibility is normally punished in a free market, and quite right. For example if car manufacturers invest an excessive amount in car manufacturing facilities, those car manufacturers and their share holders pay a price.

In contrast, in the case of the 2008 bank crisis, governments did everything they could to shield banks and depositors from their folly: depositors were rescued, and far from DISSUADING banks from lending so much, governments cut interest rates with a view to persuading banks to continue with what at least on the face of it would seem to be excessive amounts of lending!

7. Another flaw in the “have your cake and eat it / trying to make inherently unsafe loans totally safe” argument is thus.

Aggregate demand is related to the total stock of money held by the private sector. To illustrate, if the private sector has less than its desired stock, it will save in an attempt to acquire its desired stock, and the result will be Keynes’s “paradox of thrift” unemployment. Or put it another way, there must be some stock of money in private sector hands which results in a level of demand which brings full employment. Plus there will also be some stock of money which brings full employment in a “loaned on money is not insured by government” regime.

Now it might seem that if government does insure loaned out money there will be a number of benefits: e.g. the interest from additional loans will help cover the cost of running bank accounts and may even “more than cover” those costs, in which case account holders would get interest on their money.

Unfortunately the result of those extra loans is to raise aggregate demand, thus government on introducing deposit insurance would have to compensate by imposing some sort of deflationary measure, like raising taxes and confiscating a portion of everyone’s bank accounts. (I considered the latter argument in more detail in a Seeking Alpha article entitled “To enable private banks to create and lend out money…”.)

To summarise, the idea that government insurance of loaned out money brings benefits for depositors looks like a bit of a mirage: certainly that insurance enables depositors to earn more interest, but that’s at the expense of having a portion of their worldly wealth confiscated.

And that raises the question as to which is the GDP maximising arrangement: a “government insurance of loaned out money” arrangement, or second, a “no government insurance of loaned out money” arrangement.

Well it’s widely accepted in economics that GDP is maximised where market forces prevail, unless there is an obvious social reason for ignoring market forces, as there is for example in the case of kid’s education which is available for free rather than on a commercial basis.

And as explained above, government insurance only manages to beat private insurance of loaned out money because of the coercive powers of government. Those coercive powers are not part of a genuine free market. Plus there is no obvious social reason for the increased amount of lending and debt that arises where loaned out money IS INSURED by government. Indeed it is widely accepted that the total amount of debt is excessive.

Conclusion. Having government insure or stand behind deposits which are supposed to be totally safe and really are totally safe because relevant monies are not loaned on is justified. In contrast, government insurance of loaned out money is not justified.

Thursday, 24 August 2017

Silly article by Owen Jones in The Guardian.

He inveighs against austerity, which will bolster his standing as one of the political left’s darlings. Unfortunately he’s clueless.

He argues that Portugal has implemented some stimulus recently and the effects have so far been beneficial, and that allegedly shows that the austerity imposed on Portugal has been unwarranted. Well that argument would certainly be valid in the case of a monetarily sovereign country, i.e. one that issues its own currency.

Unfortunately Portugal (like Greece) is in the EZ and that means big problems, as Bill Mitchell (Australian economics prof) keeps pointing out. In particular the way the EZ deals with lack of competitiveness in a particular country is to impose austerity on it till it’s costs come down and it regains competitiveness. Of course that’s harsh, but if you have a better way of solving the latter competitiveness problem, you’ll get a Nobel prize. Otherwise shut up.

Put another way, a bit more stimulus in any country in Greece’s or Portugal’s position will bring a temporary rise in employment and GDP. Unfortunately it will also raise inflation which delays the solution to the basic problem.

Of course it could be argued and indeed has been argued that A BIT MORE stimulus would only cause minimal additional inflation, and hence that the benefits of that policy outweigh the costs. But that point is above the head of Owen Jones. Indeed, the word “inflation” does not even appear in his article.

Monday, 21 August 2017

Government borrowing is near pointless.

Milton Friedman in his 1948 paper “A Monetary and Fiscal Framework…” claimed government borrowing made no sense apart possibly during war-time - see section II: “Operation of the proposal”, 2nd para. However, he did not give very convincing reasons. Here are my attempts at a reason.

Any government can fund itself just via tax: i.e. not engage in any borrowing, as indeed Friedman said. As to borrowing, what that does is to enable some citizens to make more than the normal contribution to government spending and get paid interest on that “more than normal” chunk of money, meanwhile another lot of people can make less than their fair contribution to government spending, but they have to pay taxes to fund interest on their “less than fair share”.

So in effect, all government borrowing does is to enable the former lot of people to lend to the latter lot. But people are free to borrow from and lend to each other anyway! People lend for example when they put money into a bank term account, and people borrow when they get a mortgage for example. So does government borrowing achieve anything that is not taking place anyway, or couldn’t take place anyway?

Well government certainly seems to be an EFFICIENT intermediary between lender and borrower. Governments have draconian powers when it comes to extracting interest: that is, if you’re one of the above mentioned people who pays less than their fair share of tax and has to pay extra tax to fund interest on what you have effectively borrowed, then government can simply demand payment from you and send you to prison if you don’t pay. And in the case of a government which issues its own currency, it always has the option of printing the money needed to pay those it has borrowed from.

Those draconian powers of government explain why government debt, at least in the case of any moderately responsible government, yields such a low rate of interest: lend to government, and your money is safer than when lending to anyone else.

However, those draconian powers of government are not a normal free market phenomenon: commercial banks, non-bank corporations, and individual people when lending or borrowing do not have those powers. And if GDP is to be maximised, the only loans taking place should be loans done in accordance with normal commercial criteria.

Ergo there is no case for government borrowing. QED.

However, I wouldn’t rule out government borrowing (or borrowing by the central bank) altogether in an emergency. Indeed, to repeat, Friedman cited one “emergency” namely war. However another possible emergency is a sudden and excessive rise in demand caused for example by an outbreak of Greenspan’s “irrational exuberance”. In that case it might be difficult to effect enough deflation just via fiscal means, so having government (maybe in the form of the central bank) wade into the market and borrow at above the going rate of interest might make sense.

But to repeat, the case for government borrowing in normal circumstances seems thoroughly weak.

___________

Endnote. I have actually argued against government borrowing before, e.g. on this blog, but I think the above is a “clincher” argument I haven’t set out before.

.

Saturday, 19 August 2017

The flaws in negative interest rates.

Summary.

While negative interest rates probably raise demand, they are not an efficient or “GDP maximising” way of doing so: it’s better to simply have the state create more base money and spend that into the economy and/or cut taxes, while interest is left at a zero or slightly positive level. Two of the reasons negative rates are not efficient are thus.

First, negative rates in theory make negative output viable: not what we need. At the very least, they make “very low return on capital” forms of activity viable.

Second, governments or “states” in effect offer a service to everyone, namely what amounts to a savings bank for those who want a stock of base money (or, much the same thing, government debt). GDP is maximised where goods and services are offered at a price which is close to the cost of supplying those goods and services. And the cost of offering the latter “savings bank” service is near zero. Ergo to maximise GDP, there should be little or no positive or negative interest paid to / charged to those with accounts at the “savings bank”.

Introduction.

The reason normally given for negative rates is that rates are now so low that central banks do not have much scope for cutting rates come a recession, without going for negative rates. There is actually no need for negative rates because, as pointed out by MMTers, government of a country that issues its own currency is master of all it surveys: it can implement any level of stimulus it likes and combine that with any rate of interest it likes.

The latter “MMT” policy DOES require cooperation between fiscal authorities (i.e. politicians) and the central bank. But it’s hard to see anything wrong with two arms of government cooperating. Plus Bernanke backs the “cooperation” idea in this Bloomberg article. As for the idea that that cooperation might result in politicians getting too near the printing press, politicians can actually be kept away from the press under a “cooperative” system. Reasons are below.

Do negative rates actually work?

One problem with negative rates is that they may not actually be an effective anti-recessionary tool at all. Reason is thus.

The main idea behind negative rates is that if people are charged in proportion to their stock of cash, they’ll try to spend away that stock, which in turn should boost demand. But there’s another possibility: people may have some target amount of cash they want to hold, so if X% of that target is taken away from them, they’ll respond by saving so as to return their stock of cash to their target. And the effect of saving is to REDUCE demand!

Maximising GDP.

But a more fundamental problem with negative rates is that they may not maximise GDP. Reason is thus.

It is widely accepted in economics that GDP is maximised where products are available at a price which is near the cost of production. It makes sense to have the price of gold hundreds of times higher per kg than the price of steel: reason is it costs far more per kg to produce gold. Obviously each firm aims to make a profit, but competitive forces keep those profits down to acceptable levels normally, which results in the price of most products being near the cost of production.

Now what’s the cost to the state (i.e. government and/or central bank) of maintaining a stock of cash for each household, firm, etc? It’s almost nothing!

Incidentally I’m assuming that the state does actually make savings accounts available for all. That’s not quite the reality, but it very nearly is. E.g. in the UK there’s a state run savings bank “National Savings and Investments”. NSI provides some of the services available from a regular bank but certainly not all of those services. Plus most people in most countries are free to buy government debt, which amounts to much the same thing as putting money into a term account at a state run savings bank. (NSI actually invests only in UK government debt).

As Warren Mosler and Martin Wolf (chief economics commentator at the Financial Times) said, government debt is almost the same thing as base money.

So to keep things simple, let’s just assume the state has a savings bank for anyone wanting to keep a stock of base money. It would clearly be OK for such a bank to charge for ADMINISTRATION COSTS, as indeed existing commercial banks do.

But there is no obvious reason to charge interest on the money in such accounts, i.e. charge negative interest, if the price of the product is to be close to the cost of making the product available. Moreover, and as regards positive rates (i.e. paying interest to those holding state liabilities) Milton Friedman and Warren Mosler argued that the natural rate of interest is zero: that is, they argued that there is no reason for government to issue interest yielding liabilities. So to summarise, if we ignore administration costs, there are good reasons for thinking that neither positive nor negative interst should be paid on state run savings accounts, i.e. on “state liabilities”.

Stimulus.

But assuming the latter “zero interest” policy is adopted, how then do we implement stimulus? Well that’s easy: have the state print money and spend it (and/or cut taxes). That way the private sector ends up with a bigger stock of cash (base money to be exact), which induces the private sector to spend more. And that’s the form of stimulus Friedman advocated in his 1948 paper ”A Monetary and Fiscal Framework…”. Though he advocated the same unvarying amount of stimulus per year, an idea not widely accepted nowadays.

And if we particularly want to raise interest rates at some given level of demand (e.g. the “full employment” level of demand), that is also easily done: just “print and spend” as above but to an excessive extent, and then deal with the resulting excess demand by raising interest rates (which can be done by having government or central bank, i.e. “the state”, borrow more). That of course is not consistent with the Friedman / Mosler claim that government should pay no interest on it’s liabilities. But never mind: the point is that if a government PARTICULARLY WANTS raise interest rates, it has the power to do so. And indeed there could well be an argument for doing that in an emergency: e.g. if there was a serious outbreak of Greenspan’s “irrational exuberance”, then demand might have to be reined in in a hurry, and an interest rate hike would be one way of doing that.

Dispose of interest rate adjustments?

It was implied just above that interest rate adjustments should be abandoned (except perhaps in emergencies) and that stimulus should be done by adjusting the amount of new money created and spent. That certainly conflicts with the conventional wisdom, but it actually makes sense for the following reasons.

First, come a recession, there is no obvious reason why a fall in borrowing and lending is necessarily the cause of the problem: the cause could be a fall in some other element of aggregate demand, e.g. consumer confidence or exports. And second, even if borrowing and lending HAVE FALLEN, that could be for perfectly good reasons.

Indeed, a classic example of that was the bank crisis ten years ago: that was sparked off by excessive and irresponsible lending, followed by a sudden realization by banks that they’d lent to too many no hopers (e.g. NINJA mortgagors). So the sensible thing for them to do was rein in loans. But that caused a recession. So what did central banks do? They cut interest rates so as to encourage more lending: exactly what wasn’t needed! Might as well try curing an alcoholic by giving him crates of free whiskey!

A free market would boost the monetary base in a recession.

Another point in favor of largely abandoning interest rate adjustments and implementing base money adjustments instead is that that is what would happen in a perfectly functioning free market. That is in such a market, the price of goods, services and labor would fall in a recession. That in turn would mean a rise in the real value of the monetary base, which in turn would encourage spending.

That phenomenon does not work too well in the real world because as Keyes put it, “wages are sticky downwards”. But never mind: instead of raising the value of each dollar making up the base, the NUMBER OF dollars making up the base can be increased instead.

Negative output.

Having claimed above that GDP is not maximised where employers make a charge for a product which is not related to costs, it should be possible to point to exactly how that failure to maximise GDP comes about where the state makes an unwarranted charge to those holding state liabilities, i.e. charges negative interest. Well here goes.

Say I can borrow at minus 4%. I could then buy 100 houses, keep them for a year, burn down two of them just for fun, sell the remaining 96, and come away with a 2% profit! Crazy: that amounts to what might be called “negative output”.

Of course that’s a silly example. But there is a serious point there: under a negative interest rate regime, forms of negative output or “wealth destroying” output then become viable. At the very least, forms of output become viable which would not be viable at the Friedman / Mosler zero rate, or a higher rate.

Politicians and the printing press.

Having suggested it can be an idea for the state to simply print money and spend it and/or cut taxes, there is an obvious problem there namely that that requires cooperation between the central bank and politicians, thus politicians get closer to the printing press. Does that matter?

Well the evidence seems to be that in most countries the degree of independence of the central bank (i.e. how close it is to politicians) does not influence inflation – see chart below which is taken from an article by Bill Mitchell.

However, like most people I suspect, I’d rather keep politicians away from the press. And doing that under a regime where it is possible to “print and spend” is not difficult. All that needs to be done is to give the responsibility for determining the amount to be printed to the central bank (or some independent committee of economists), while politicians retain the right to determine what proportion of GDP goes to public spending. Indeed, that’s not vastly different from the existing system in that an independent central bank has the last word on how much stimulus there shall be: e.g. under the existing system, if the central bank thinks politicians have implemented too much fiscal stimulus, the central bank well negate that by raising interest rates.

Under a system where the central bank determines the amount of stimulus, but stimulus is effected simply by creating and spending new base money (or cutting taxes), the central bank might say “public spending needs to exceed tax by 2% of GDP this year and here’s the money that enables that to be done”. Politicians would then have the choice as to whether to effect that by having public spending equal to 30% of GDP and tax equal to 28% of GDP. Or they could go for 40% and 38%, etc.

And what do you know? That’s exactly the system advocated by Positive Money, the New Economics Foundation and Prof Richard Werner in this work. Bernanke also expressed sympathy with that sort of system. To be exact, in this Fortune article, Bernanke suggested the central bank should determine the AMOUNT of money to be created and spent, while (as suggested above) politicians take the essentially POLITICAL decisions: whether to distribute the largess in the form of more public spending or tax cuts, and if the former, how much goes to education, health, defence, etc. See para starting “A possible arrangement…” halfway down.

Sunday, 13 August 2017

A not very clever article on banking by Tim Congdon.

It’s this recent article in the Telegraph entitled “Our zeal to punish the bankers only stoked the Great Recession”.

Tim Congdon has the impressive sounding title of: “Chairman of the Institute of International Monetary Research at the University of Buckingham”. Unfortunately his ideas have never been equally impressive, as I’ve explain in earlier articles on this blog.

The basic point he has banged on about for many years (and in his Telegraph article) is that GDP is related to the money supply, ergo (so his argument goes) if the money supply is expanded, GDP rises. Ergo it is essential for commercial banks to be encouraged to lend more (as the title of the above article implies).

The flaws in that idea should be obvious enough to anyone with a decent grasp of economics, but for the benefit of readers not sure what the flaw is, I’ll run through it.

Two sorts of money.

The problem with Congdon’s argument is that there are two very different forms of money: central bank issued money and private bank issued money. The former is a net asset as far as the private sector is concerned. To illustrate, one way of expanding the private sector’s stock of CB money would be for the CB to print dollar bills or pound notes and to have government hand them out in the form of extra unemployment benefit or increased state pensions.

That would induce pensioners etc to spend more.

In contrast, there is commercial bank issued money. That money comes into being when a commercial bank grants a loan. But note that while it’s nice for the borrower to have $X at their disposal as a result of the loan, the borrower is of course indebted to the bank. So on balance the borrower is no better off (unlike the above mentioned pensioners.) Or to quote a commonly used phrase (which Congdon has presumably not caught up with), commercial bank issued money “nets to nothing”. Certainly there is no mention of the two basic forms of money in Congdon’s article.

Congdon is correct to suggest that increasing either form will increase demand. The reason why pensioners etc spend more when they find more pound notes in their wallets is obvious enough. As to how and why increased loans by commercial banks raises demand, that should be equally obvious: if I borrow $Y with a view to having a house built, that will increase demand for bricks, timber, bricklayers, plumbers and so on.

For more details on how, why and the extent to which increased bank loans increases demand, Steve Keen’s short and very readable book “Can we avoid another financial crisis” is a good source.

To summarise so far, if we want to increase demand, that is easily done EITHER by expanding the stock of central bank money or the stock of commercial bank money. And the way governments normally induce commercial banks to lend more to their customers is to cut interest rates.

Why expand the amount of dodgy private money?

There is however a glaring problem with privately issued money: the private banks which issue it, not to put too fine a point on it, are big time criminals. To be more exact, total fines and out of court settlements paid by US banks in recent years in the US comes to a staggering $200bn or so. And then there’s the small matter of the risky practices they indulged in which caused the worst recession since World War II.

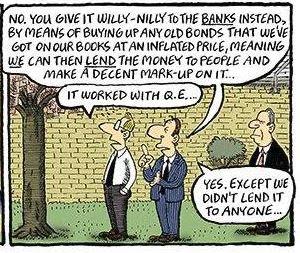

So, contrary to Congdon’s suggestions, there are EXTREMELY GOOD reasons for clamping down on various commercial bank practices. And as for Congdon’s complaint that that exacerbates recessions, the simple answer to that is to expand the private sector’s stock of CENTRAL bank money: exactly what various governments have actually done in recent years.

It could be argued that the WAY in which the private sector’s stock of central bank money has been expanded, namely QE, has not been very effective because QE is just an asset swap. That is, the central bank prints $Z worth money and buys up $Z of government debt. And from that you might concluded that private sector net assets have remained about constant.

Actually that’s a bit misleading. Reason is that prior to QE and during the initial stages of QE there was a much larger than normal government deficit. And a deficit consists of: “government borrows $A and gives lenders $A of government bonds and spends $A back into the private sector. Lo and behold the private sector’s stock of paper assets rises by $A! Then comes QE, which consists of “central bank prints $A and buys back $A of bonds. Net result: the private sector has $A more cash (just like the above mentioned pensioners).

And finally, for anyone interested in delving a bit further into Congdon’s ideas, there is a transcript of a discussion between him and Prof Robert Skidelsky here in which Skidelsky tries to explain to Congdon the error of his ways.

Wednesday, 9 August 2017

Sunday, 6 August 2017

Saturday, 5 August 2017

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)