Commentaries (some of them cheeky or provocative) on economic topics by Ralph Musgrave. This site is dedicated to Abba Lerner. I disagree with several claims made by Lerner, and made by his intellectual descendants, that is advocates of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). But I regard MMT on balance as being a breath of fresh air for economics.

Saturday, 28 April 2018

Job Guarantee buffer stock nonsense.

A buffer stock is a stock of some commodity, e.g. crude oil or wheat, which is held with a view to ironing out fluctuations in the price of the commodity. For example when the market price rises too fast, some of the stock is sold into the market so as to temper the price rise.

One of the central ideas behind JG, at least as claimed by Bill Mitchell and others, is that the unemployed and those doing JG jobs act as a buffer stock, and that allegedly explains why JG works. E.g. see Bill Mitchell’s series of articles “Buffer stocks and price stability” parts 1-5.

OK let’s examine the “buffer stock” idea, and we’ll start with rising rather than falling prices.

When aggregate demand rises, demand for labour also rises and that clearly might result in the price of labour rising, and hence in general inflation. However, given a “buffer stock” of unemployed individuals, clearly some of those people will be able to fill vacancies as they arise, which of course prevents the price of labour rising. So far so good: the buffer stock analogy seems to work.

But what happens when the stock of people who are unemployed shrinks too far? Well inflation often takes off when there is still an extremely large buffer stock or stock of unemployed individuals. To be more exact inflation can take off when that stock equates to roughly 5% of the workforce. I.e. even though there may be a million or more people in the much vaunted “unemployment buffer stock” in a country with the population of the UK, they do not necessarily temper wage or price rises.

And the reason for that is not too difficult: it’s that as unemployment falls, the chances of an employer finding the sort of labour required (particularly skilled labour) on each local labour market shrinks. But that’s in stark contrast to a buffer stock of wheat or crude oil: in the case of the latter, as long as is SOME stock left, it can be sold to temper price rises.

So the buffer stock analogy would seem to be rather a long way from being a perfect analogy. But let’s move on to falling prices and wages.

Falling prices and wages.

If there is a gross excess supply of labour, i.e. a larger than normal number of people who are unemployed, then given a perfectly functioning free market, the price of labour would fall. But the price of labour just doesn’t fall to any great extent: indeed as Keynes famously said, “Wages are sticky downwards.” So why is that?

Well according to the buffer stock theory, it’s because government buys up surplus labour. In the case of the unemployment buffer stock, government offers unemployment benefit to the unemployed. And in the case of JG, government offers temporary subsidised jobs.

Only problem there is that while clearly the availability of unemployment benefit PARTIALLY explains the failure of wages to fall in recessions, the pay offered via unemployment benefit is pretty miserable in most countries. So that “benefit” explanation is a bit feeble. And in fact research by Truman Bewley indicates that the main reason wages do not fall in recessions is the extreme bad will created between employer and employee if an employer DOES cut wages: it is simply not worthwhile for an employer to try to cut wages in a significant proportion of cases. Churchill’s attempt to cut coal miners’ wages in the 1920s is an example: it resulted in a year long strike.

So once again, the buffer stock idea is a bit of an irrelevance.

So if the buffer stock idea doesn’t explain why JG might work, what is the explanation? Or to put it more precisely, how can JG cut unemployment even when unemployment is as low as it is supposed to be able to go before inflation kicks in in a serious way? (And incidentally, JG is not the best solution for unemployment when unemployment is ABOVE the latter level: a straight rise in demand is the best solution, though clearly JG can help.)

Well one reason inflation rises if demand is boosted when unemployment is at the “inflation tipping point” is the reduced aggregate labour supply that occurs as a result: that is, if unemployment is at the tipping point and demand rises, then the number of individuals looking for work declines. That is, the supply of labour to firms who still have vacancies declines, which in turn obviously induces employers to raise wages (or give in more easily to union demand) with a view to attracting more labour. Inflation is exacerbated.

Of course that’s not to say that some of those IN WORK are not seeking work in the sense of looking out for better jobs. But certainly, when demand rises and unemployment falls, the number of those who are what might be called “desperate for work” declines.

However, if JG jobs are created where the pay is not too generous, and as a result, those concerned seek regular jobs with the same effort as when unemployed, then JG jobs will not exacerbate inflation - at least not as a result of the above labour supply point.

So that’s one explanation as to why JG can work. There are others, which I’ve set out elsewhere, but that’ll do for now.

Friday, 27 April 2018

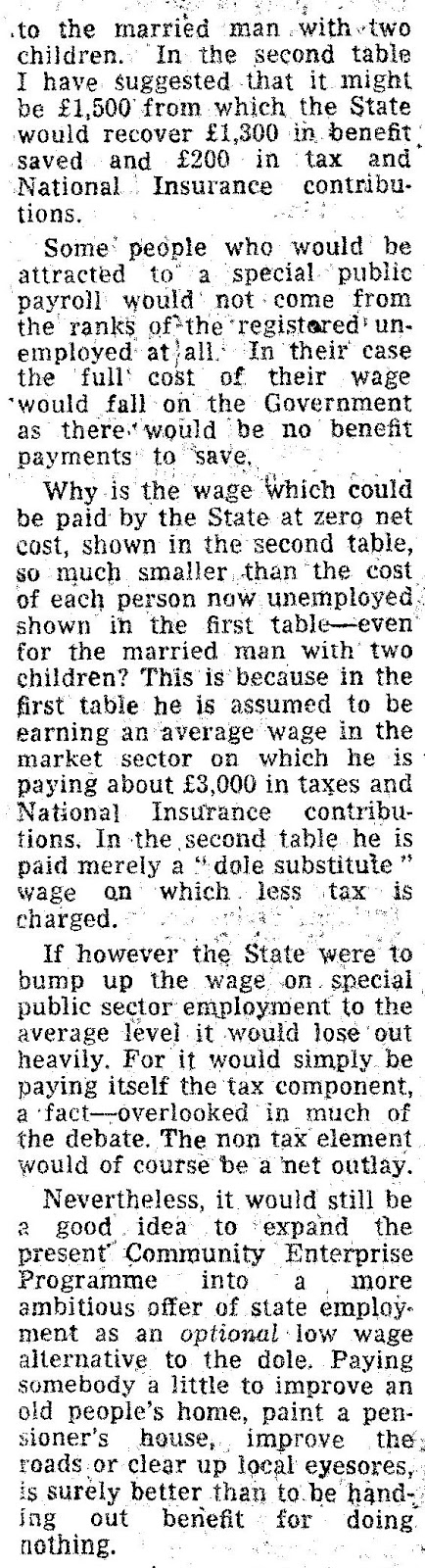

Financial Times article on Job Guarantee type schemes from 1981.

The article is by Samuel Brittan, former chief economics correspondent of the FT, and is entitled, "The cost of employing the unemployed". Apologies for the quality, but it comes from scanning a photocopy of the original article which has been in my attic for almost 40 years...:-)

If you want to jump straight to his conclusion, he is cautiously in favor of JG, but wants it fairly limited in scale.

Thursday, 26 April 2018

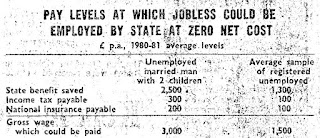

UK Job Guarantee type schemes in the 1970s.

This is an extract from “The evolution of special employment measures.” by Paul Gregg, published by the NIESR.

Wednesday, 25 April 2018

Having the central bank decide the size of the deficit is “undemocratic”?

Richard Murphy claims it would be "undemocratic" for the central bank to control the size of the budget deficit. See the two paras starting "In other words..." in Murphy’s article entitled “IPPR’s new macroeconomic report: in need of revision.” (Incidentally Ann Pettifor makes the same “undemocratic” claim.) That "undemocratic" claim by Murphy does not actually stand inspection and for the following reasons.

It would be perfectly feasible, and arguably desirable, to have an arrangement under which the central bank (CB) controls not just interest rates, but also the size of the budget deficit. That arrangement is actually advocated in a recent IPPR work which Murphy considers in his article. It is also advocated by Positive Money.

An ever popular argument against that arrangement is that since under existing arrangements, it’s the finance minister / treasury / politicians (FTP) that control the size of the deficit, and since politicians are democratically elected, ergo the above “CB controls the deficit” must be less democratic. That’s actually false logic, and for the following reasons.

Politicians have two motives for expanding the deficit, one of which is totally unacceptable: that’s the desire to ingratiate themselves with voters by funding public spending via borrowing so as to get future generations to foot some of the bill for today’s spending. Trump is doing that right now.

Another motive (an entirely acceptable one) is to bring about stimulus. But there’s a problem there, namely that independent CBs (or at least NOMINALLY independent CBs) have the power to override the latter stimulatory effect via interest rate rises. Thus the alleged “democratic” right that politicians have to boost stimulus is one big illusion!!!

To summarize, the whole idea that FTP has any sort of useful “democratic” right deriving from the right to determine the size of the deficit lies in ruins: i.e. when that right is exercised, either its motivated by a desire to rob the next generation, or it’s a futile attempt to boost stimulus, given that the CB has the final say on stimulus.

Ergo, having the CB decide the size of the deficit, rather than FTP doing so, has no effect on “democratic” rights. In particular, note that having the CB decide the size of the deficit most certainly does not take away from politicians the right to decide what proportion of GDP is allocated to public spending, or how that is allocated as between education, defence and so on. It is only the DIFFERENCE between total government income (from tax) and government spending that the CB controls.

Sunday, 22 April 2018

The argument for a permanent zero interest rate.

Introduction.

If you like simple original economics ideas like E=MC2, then the permanent zero interest rate idea might interest you. So let’s run thru the arguments for this idea. As with Einstein’s famous equation, while the end result is simple, the arguments leading to it are not quite as simple. However, you don’t need to be a genius to understand the arguments for a permanent zero interest rate.

That idea amounts to saying that government and central bank (I’ll refer to that pair of entities as “the state”) should issue a form of money, i.e. base money, but should not pay interest to anyone for holding that money: i.e. it’s the idea that there should be no government debt.

Milton Friedman briefly suggested the idea in 1948*. See his para starting “Operation of the proposal…”.

The idea was also advocated by Warren Mosler** in 2005, and Bill Mitchell*** in 2011.

Needless to say I think I can explain the reasons for a permanent zero rates better than the above three individuals – else I wouldn’t bother writing this article! So here goes.

Demand and the stock of base money.

It is reasonable to assume that aggregate demand will vary with the size of the stock of base money held by the private sector. That is, all else equal, when a household is given more money, its weekly spending rises, ergo give more money to every household, and demand will rise.

Note that is not the same as saying that demand is related to the total stock of money: the bulk of the money supply is created by commercial banks, and for each dollar of money they issue, there is a corresponding dollar of debt. Thus a rise in the stock of that type of money probably has little effect on demand: indeed, a rise in that stock is probably the RESULT of a rise in the private sector’s desire to do business (e.g. a desire to borrow and invest in machinery or in a larger stock of finished goods for sale).

It follows that the optimum stock of base money to issue is the amount that keeps the economy operating as near capacity as possible, without causing excess inflation.

Now government can of course issue more than that stock of base money, but if it does, demand will probably become excessive, which means government will need to offer interest to “money holders” with a view to persuading them not to try to spend away their excess stock of base money.

But the effect is an entirely artificial rise in interest rates! And that’s an important defect in the latter “excess stock of base money” scenario. The defect is that it is widely accepted in economics that the GDP maximising price for anything is the free market price, and that presumably goes for interest rates. Ergo, the above “excess stock of base money” scenario will not maximise GDP. (There are of course exceptions to the latter “free market is best” idea: that is we overrule market forces where it is clear that social considerations should overrule the free market. E.g. kid’s education is available for free. But in the absence of obvious social considerations, the normal rule is: “the free market price is best”.)

Having hopefully established that a zero government borrowing regime is best, there are numerous matters arising from that claim and apparent problems with the claim. Some of those problems will now be considered.

A permanent zero rates rules out interest rate adjustments.

The answer to that criticism is that demand can perfectly well be regulated by fiscal means as well as monetary means (e.g. interest rate adjustments). Plus it is clear that neither method of adjusting demand works in quick or predictable way, thus abandoning one of those methods of demand adjustment would do not harm at all, at least in principle.

Also abandoning interest rate adjustments does not mean ruling out monetary instruments altogether: that is, it would be perfectly possible to abandon interest rate adjustments, while implementing stimulus by having the state print base money and spend it (and/or cut taxes) as necessary, and that would clearly increase the private sector’s stock of base money, which is monetary policy of a sort.

Government should borrow so as to invest.

The popular idea that government should borrow so as to invest in infrastructure and the like obviously clashes with the above claim that government should borrow nothing. In fact the arguments for the latter “popular” idea don’t stand inspection.

First, the average small business proprietor would fall about laughing at the idea that investment justifies borrowing: for example if a taxi driver wants a new taxi and happens to have enough spare cash to buy it, why would he or she borrow? That is, why pay interest to someone when you don’t need to? And the state has a near inexhaustible supply of cash: first the taxpayer, and second, government or “the state” can print money (though clearly money printing cannot be take too far).

Second, education is one huge investment, but for some bizarre reason, while the idea that borrowing should fund infrastructure investment is popular, no one ever suggests the entire education budget should be funded via borrowing.

Third, the lack of any sort of logical relationship between borrowing and investment is further underlined by the fact that it can make sense to borrow to fund consumption. For example there are doubtless thousands of married couples whose children have left home and who plan to move into a smaller home but don’t want to do so quite yet. If some of those couples want to borrow money this year to go on a world cruise, then pay the money back out of the proceeds of sale of their existing house in a couple of years’ time, that would make sense.

The conclusion of this section is that the idea that investment justifies borrowing is nonsense. The real justification for borrowing is a shortage of cash.

Giving politicians the right to borrow is risky.

When politicians have the right to borrow, it’s pretty obvious what they’ll tend to do: borrow now with a view to ingratiating themselves with voters, with the cost of that ploy being loaded onto future generations. David Hume writing almost 300 years ago spelled out that danger very clearly. As he put it:

“It is very tempting to a minister to employ such an expedient, as enables him to make a great figure during his administration, without overburdening the people with taxes, or exciting any immediate clamours against himself. The practice, therefore, of contracting debt will almost infallibly be abused, in every government. It would scarcely be more imprudent to give a prodigal son a credit in every banker's shop in London, than to impower a statesman to draw bills, in this manner, upon posterity.”

Government borrowing spreads costs across generations?

An apparent merit of government borrowing for infrastructure is that it spreads the cost over the generations that benefit from the relevant investments. The flaw in that idea is that idea assumes time travel is possible: that is, it is not physically possible to build a bridge in 2018 using steel and concrete produced by the blood, sweat and tears of those living in 2030.

That point about time travel might seem to conflict with David Hume’s point above about people today borrowing from “posterity”, i.e. future generations. The explanation is that a country can only in fact succeed in imposing costs on future generations to the extent that it borrows from abroad. Thus the extent to which David Hume’s point is valid is a bit limited.

To illustrate, a country clearly benefits in the short term if the steel for a bridge is supplied by another country. That steel production requires blood, sweat and tears to be expended in the other country in 2018 for example. But when that debt is paid back, real goods (perhaps steel) has to be shipped the other way, which imposes a “blood, sweat and tears” cost on the country where the bridge is build.

Exactly the same point applies to a household. If one member of a household lends to another, there is not net benefit for the household as a whole. But if the loan comes from OUTSIDE the household, the household can enjoy a temporary standard of living boost, which will have to be paid back at some point.

And there is another problem with the “spread across generations” idea, namely that the government of most countries invest in infrastructure and so on, thus if every country borrows from other countries to fund their investment, the latter benefits approximately all cancel out!!

Borrowing to smooth out receipts from income from tax.

One excuse for government borrowing is that allegedly government needs to borrow so as to smooth out receipts from tax. In fact if government is short of funds for a few months, there is nothing to stop it (assisted by the central bank) from simply printing money to make good the temporary shortfall.

It might seem that that would lead to the private sector having an excessive stock of base money at particular times of the year, which in turn could result in excess demand, which in turn needs to be damped down by government borrowing. The answer to that is that if a firm or individual knows they will have to pay about $X to the tax authorities in six months’ time, they are unlikely to blow that money on consumer goodies! Thus there is little need for the latter “damping”.

The political problems of “fiscal policy only”.

Having suggested above that interest rate adjustments can be abandoned, that clearly implies that fiscal adjustments take more of the burden, which could involve political problems. E.g. if an economy is overheating, that can be dealt with by rise in income tax plus an interest rate rise, whereas if it’s just the income tax rise that does the job, then clearly the tax increase will need to be larger, and that could prove unpopular.

The answer to that little problem is that a permanent zero rate does not need to be 100% permanent. That is, if there is no government debt, and a temporary interest rate rise is required in order to get round the latter sort of political problem, the central bank can always wade into the market and borrow at above the going rate. But certainly the objective should be to return the “no state borrowing” scenario as soon as possible.

Government borrowing facilitates private borrowing.

A final possible justification for government borrowing is one which I have not seen anyone else spell out, but it’s a possibility. It goes like this.

Government borrowing actually facilitates lending by the cash rich to the cash poor. That’s because the rich are clearly the ones who tend to lend to government, while the fact of that lending enables the poor to pay less tax, although taxpayers in general have to fund interest on government debt, and the poor do pay significant amounts of tax. Thus in effect, government borrowing enables the rich to lend to the poor.

Of course the rich are free to lend directly to the poor and indeed they do so, big time. But an advantage of “borrowing via government” so to speak might seem to be that the process is relatively efficient: witness the low rates of interest earned from government debt.

Unfortunately there is a snag with that argument which is that the latter efficiency derives from governments coercive powers: that is, government’s powers when it comes to collecting tax are similar to the powers enjoyed by the Mafia. And if the state has any problems repaying its debts, it can always resort to printing money in excessive amounts. Thus that method whereby the rich can lend to the poor does not represent fair competition with more traditional methods of lending. So the conclusion is that there is not much to be said for the latter “government borrowing facilitates private borrowing” idea.

_______________

* “A Monetary and Fiscal Framework for Economic Stability”, American Economic Review.

** “The Natural Rate of Interest is Zero.” Journal of Economic Issues.

*** “The Natural Rate of Interest is Zero.” Modern Monetary Mechanics.

Thursday, 19 April 2018

Is Mariana Mazzucato saying anything new?

To judge by this review of her book in “Nature”, Mazzucato is not saying anything very original. Obviously I need to read her book before passing final judgement on it. But life is short: I do not have time to read all the books I’d like to, so I normally read ARTICLES by authors before deciding to read their books so as to get some idea as to whether their books are worth reading. (Title of the Nature article is, "How to re-tool our concept of value.")

However, the REASONS for the popularity of her book are obvious: the ideas in it have an obvious appeal for the socially concerned, economically not very literate section of the political left. And we are talking about a VERY LARGE number of people there.

I’ll run thru some of the points in the Nature article in the order in which they appear in the article.

The first para mentions the need to deal with “climate disruption”. Well about 90% of the population have worked out that climate change is a serious issue! That’s why the world is spending billions on wind and solar energy production!

According to the second para, Mazzucato is keen on the idea that the market price for goods and services is not a good measure of their value. Well we all worked that out a century ago, didn’t we? That’s why don’t let alcoholic drinks change hands at free market prices: we place a heavy tax on alcohol because of the damage it does.

And the dodgy nature of market prices also explains why we grab vast amounts of money off taxpayers and spend it on public expenditure items like education and health care. That process amounts to over-ruling market forces.

Next, according to the para starting “The international system…”, Mazzucato apparently claims “only goods and services sold in markets are counted” when it comes to measuring GDP. That’s nonsense: public sector spending is included as well.

Next, we are told the market “stokes inequality”. Well of course: the market price for someone with a low IQ and a drink or drugs problem is often around zero. But we don’t let them starve (though of course there’s always the odd few who fall thru the social security safety net, even in Europe).

The second last para starts "Mazzucato deconstructs several other key trends. These include how the financial sector’s “casino capitalism” mislabels market speculation as the creation of value". Well that idea is not original: in 2009, Adair Turner (former head of the UK’s Financial Services Authority) said that much of what the City of London does is “socially useless”.

Monday, 16 April 2018

Millions to become unemployed just because politicians know nothing about economics.

As this Brookings Institution article rightly says, come the next recession, the Fed may have limited scope for cutting interest rates because they are already very low, and fiscal stimulus may be limited because politicians are worried about the debt and the interest paid on it. Indeed, that happened to some extent in the recent recession. (Title of Brookings article: "Tax and spending legislation disarms us against next recession.")

So what are those pig ignorant politicians (and quite a few pig ignorant economists) worried about? Well first it might seem that as the debt rises, so too will the rate of interest paid on the debt. But that’s unlikely because assuming stimulus really is needed and assuming the Fed recognises that, then the Fed will stop any such interest rate rises by printing money and buying up government debt. Indeed, there’s nothing to stop the Fed cutting interest rates to zero or very near zero. So that’s the alleged “interest on the debt” problem solved.

But politicians will doubtless have another worry: what happens to interest on the debt when the recession is past, and the debt is significantly bigger? Well if debt holders are happy to continue holding debt at a relatively low or near zero rate of interest, then there isn't a problem.

On the other hand, if they start demanding a significantly higher rate, then all the Fed needs to do is to print money and pay off debt holders as debt matures, and tell debt holders to get lost. Of course that money printing could be too inflationary. But that’s not a problem in principle: the Fed just needs to tell politicians to raise taxes or cut public spending with the Fed “unprinting” the money collected or saved.

Note that the latter strategy would have NO EFFECT on demand or numbers employed, strange to relate. That is, while raising taxes normally cuts demand, the purpose of the cut in demand here is simply to keep demand down to a level where it does not cause excess inflation. In other words, in real terms, there would probably be no effect on demand at all.

Unfortunately that’s not the way politicians or voters would see it. Politicians would balk at the latter tax increase. Thus politicians’ ignorance about economics would scupper the latter strategy. And as a result, the above mentioned fiscal stimulus may well not be implemented at all.

Ultimate effect: millions become unemployed because of politicians’ ignorance about economics. And if that isn't a catastrophically stupid way to run a railroad, I don’t know what is.

The solution, as advocated by Positive Money the UK based economics think tank, is to separate politics from economics. That is, have politicians take strictly POLITICAL decisions, like what percent of GDP to allocate to public spending and how that is split between education, defence, etc), while decisions on the size of stimulus packages are taken by economists.

Thursday, 12 April 2018

Wednesday, 11 April 2018

Feeble criticisms of MMT by Thomas Palley.

Palley tries to criticize MMT in an article entitled “Modern Money Theory (MMT) vs. Structural Keynesianism”.

His first criticism (his section 1A) is actually valid or at least part valid. That’s the idea that MMT is just Keynes writ large. Others (e.g. Simon Wren-Lewis) have made the same criticism. That criticism is fair enough, but have you ever tried reading Keynes General Theory (his most famous book)? It’s near incomprehensible. In contrast, MMT takes the basic Keynsian ideas and sets them out in a relatively clear manner.

Next (section 1B) Palley says “First, MMT economists used to say it is easy to have full employment without inflation. I don’t think that is true. As you edge toward full employment, inflation will increase.”

In fact MMTers have never denied that inflation puts a limit on the amount of stimulus that can be implemented, i.e. that inflation tends to rise as full employment is approached.

But I agree with Palley’s point that some MMTers appear to play fast and loose with deficits and appear to suggest that governments can simply print money willy nilly.

Next, Palley says, “MMT economists tend to say the central bank should park the interest rate at zero and forget about it. I think that is crazy. It is throwing away an important economic policy tool, and it would likely promote dangerous asset price inflation..”.

Wrong. Warren Mosler (and indeed Milton Friedman) backed a zero interest regime, and it’s an idea I agree with, but it’s not an idea widely promoted in by MMTers.

Re “asset price inflation”, the first flaw in that idea is that asset bubbles are not exactly unknown given more normal rates of interest: it was an asset price bubble while interest rates were at normal levels that was largely responsible for the bank crisis ten years ago!

Second, if we had a permanent zero rate, any amount of deflation (i.e. cut in AD) can be implemented via fiscal means: to be exact, the state can in principle always raise taxes and “unprint” the money collected. Of course that is difficult to do in a scenario where a bunch of economic illiterates known as “politicians” are determined to have a say in how large the deficit / surplus should be, but IN PRINCIPLE, the zero rate idea is doable.

Moreover, a permanent zero rate does not mean we would have to stick to and EXACTLY zero rate of interest all the time: that is, if a sudden dose of deflation were needed, a temporary rise in interest rates could easily be implemented, with the objective being to return to zero as soon as possible.

But the real killer argument for a permanent zero rate is that it brings about a genuine free market rate of interest: the rate of interest which maximises GDP. That’s on the grounds that, as is widely accepted in economics, the GDP maximising price for anything is the free market price, unless there is a clear social case for a non free market price (e.g. kids’ education is available for free because of the obvious social benefits).

So why does a zero rate give us a genuine free market rate of interest?

Well clearly the state or central bank performs a useful service is issuing enough money to induce the private sector to spend at a rate that brings full employment. (The more money people have, the more they tend to spend.) But is there any point in the state issuing so much money that it then has to offer interest to holders of that money interest in order to persuade them not to spend away their excess stock of money? Absolutely none!

That process, i.e. upping the rate of interest just to persuade people with large wads of $100 bills not to spend those bills, so to speak, clearly results in an artificially high rate of interest. Indeed that artificially high rate is absurd in that it results in forcing every mortgagor to pay an artificially high rate of interest on their mortgage most of the time just to enable the state us use interest rate cuts to adjust demand.

Exchange rates.

Next Palley says “MMT economists say all a country needs is a floating exchange rate, and then it can use money financed budget deficits that push the economy to full employment.”

Well what’s wrong with floating exchange rates!!!! The US, UK and Eurozone have a floating rate. It’s news to me that that’s some kind of disaster.

And MMTers do not (to repeat) say “Let’s print money willy nilly with inflation going thru the roof, and with the exchange rate constantly depreciating.”. Their basic claim (as Pally himself points out) is that demand should be as high as is consistent with acceptable inflation. As to the exchange rate, that can be left to find its free market level at that “acceptable” level of inflation.

And finally, in his section 2A, Palley says “MMT is best understood as political polemic…”. Well there’s some truth in that: i.e. campaigning for something substantially different to the existing order (e.g. a permanent zero rate) is “political” by definition. But what’s wrong with arguing for a system which is substantially different from the existing and clearly flawed system? The first people to advocate central banks were “political polemicists”. Now they’re part of the establishment.

On the other hand Palley says MMT is simply Keynes writ large. Well to the extent that that’s true, MMT is advocating nothing new, so it’s not political!!!

Sunday, 8 April 2018

The IMF is still away with the pixies…:-)

Bill Mitchell (Australian economics prof) published an article in 2013 entitled “IMF still away with the pixies”, which claimed the IMF had a poor grasp of macroeconomics. Unfortunately things have not improved much if a recent article published by the IMF is any guide. It’s entitled “Climbing out of debt.”

The argument in the article runs as follows.

National debts are relatively high right now, and given that interest rates may return to their pre-crisis levels in the near future, that means a high interest payment burden on taxpayers unless something is done to cut debts. And that in turn means taxes need to be raised or public spending cut. Thus the question arises as to which of those two options is the better: raising taxes or cutting public spending – in particular, which has the bigger effect so far as reducing GDP goes.

The IMF authors claim that public spending cuts are in fact the better option. Their concluding paragraph reads:

“The bottom line is that reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio depends a lot on how the budget deficit is corrected…….Deficit reduction policies based on spending cuts, however, typically have almost no effect on output, so they are a sure bet for a reduction in debt to GDP.”

That whole argument is actually nonsense on stilts, basically because there is no need for government to borrow at all. The bulk of public spending is already funded via tax, and it would be easy to fund ALL public spending via tax (plus a bit of good old money printing – of which, more below).

But let’s examine that point in more detail.

First, far from there being any particularly good reasons for funding public spending via borrowing, politicians’ motive for doing so is in fact suspect: one of politicians’ main motives is to ingratiate themselves with voters by imposing the burden of today’s public spending on future generations. As David Hume writing over 200 years ago put it:

“It is very tempting to a minister to employ such an expedient, as enables him to make a great figure during his administration, without overburdening the people with taxes, or exciting any immediate clamours against himself. The practice, therefore, of contracting debt will almost infallibly be abused, in every government. It would scarcely be more imprudent to give a prodigal son a credit in every banker's shop in London, than to impower a statesman to draw bills, in this manner, upon posterity.”

Next, the IMF authors’ toying with different effects on GDP coming from public spending cuts as compared to tax increases is nonsense because GDP should ideally always be kept at the “capacity” level: the level where unemployment is minimised in as far as that’s compatible with avoiding excessive inflation. And indeed that is more or less where the economy is right now: unemployment is at near record low levels.

Now if the economy is at or near capacity with inflation not a serious problem, why are IMF people even contemplating reducing GDP just so as to reduce the amount of interest paid on the national debt? If it’s desirable to cut that interest rate burden that’s very easily done without there being any effect on GDP at all: just have the central bank print money and buy up government debt! Or if you like, continue with QE.

Of course that might have too much of a stimulatory or inflationary effect, but that effect is easily countered by raising taxes and “unprinting” the money collected. Indeed Milton Friedman and Warren Mosler argued that governments should never incur any debt at all: i.e. they argued that all public spending should be funded via tax. Thus the above “continue with QE and raise taxes as necessary” is simply a movement towards the set up advocated by Friedman and Mosler (FM).

Incidentally, note that while raised taxes normally make households worse off, that’s not the case here because the sole purpose of the latter tax is to cut demand to a level that the economy can meet without excess inflation. I.e. in that that tax deals with excess inflation, it probably makes households BETTER OFF.

There are absolutely no strictly economic or technical problems involved in the latter “buy up government debt and raise taxes” ploy. The big problem is POLITICAL: that is, politicians, 90% of whom do not have even the most basic qualification in economics, think they are qualified to decide how much debt government should incur and how large the deficit should be.

Another apparent problem with adopting or moving towards the FM “no borrowing” scenario, is that if there is no government debt, then it is more difficult for central banks to control interest rates (central banks normally control interest rates by buying and selling government debt).

I.e. stimulus would be effected mainly or exclusively by creating more money and spending it (and/or cutting taxes), and given the snail’s pace at which politicians decide how to spend extra money, things would need to be speeded up there. But there are no strictly technical or economic difficulties there.

For example in the UK, it is common for the finance minister to announce changes to the sales tax, VAT, and the tax on alcohol and fuel, and to effect those changes within 24 hours. That is not particularly democratic, but it is quick, plus there is nothing to stop other democratically elected politicians, in particular UK House of Commons debating the matter at their leisure, and pushing for a change to how taxes are collected over the long term: e.g. more coming from income tax and less from VAT.

Ben Bernanke actually gave his blessing to a system of that sort, i.e. a system where the Fed decided the SIZE OF the deficit (i.e. how much new money to create) while politicians decided EXACTLY HOW to spend that money (more on education versus more on infrastructure versus more on tax cuts, etc). See para starting “A possible arrangement…” in his Fortune article entitled “Here's How Ben Bernanke's "Helicopter Money" Plan Might Work”.

And finally, even if there is no government debt, there is nothing to stop a central bank raising interest rates if it wants to simply by wading into the market and borrowing at above the going rate. Various central banks may not be allowed to do that under the existing legislation in various countries. But there is not good reason for central banks not being allowed to do that. Thus the law can easily be changed.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)