Commentaries (some of them cheeky or provocative) on economic topics by Ralph Musgrave. This site is dedicated to Abba Lerner. I disagree with several claims made by Lerner, and made by his intellectual descendants, that is advocates of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). But I regard MMT on balance as being a breath of fresh air for economics.

Tuesday, 19 December 2017

Sunday, 17 December 2017

Pigou subsidies.

Bit arcane this – so don’t say you weren’t warned.

A Pigou subsidy is an idea I hadn’t come across till Nick Rowe draw the attention of all and sundry to it on Twitter. It’s the idea that a gift, particularly a gift by the rich to the poor, involves a positive externality, i.e. a net benefit for society as a whole. Ergo, the rich should be given a financial inducement to give, in rather the same way as negative externalities like pollution are DISCOURAGED by taxing the polluter.

Nick Rowe’s tweet:

EconTwitter: It is really bugging me that I can't get my head straight on this stupid exam Q: "Gifts create a positive externality (for the recipient), so a Pigou subsidy is needed to get the optimal amount of giving". Discuss.— Nick Rowe (@MacRoweNick) December 16, 2017

My answer, for what it’s worth, was thus.

Take the simple case of a country divided into two classes, rich and poor. Donations by a rich person to a poor person bring net benefits. Say the benefit is equal (in terms of dollars) to the gift. But to induce a rich person to give, they must be given a Pigou subsidy equal to the amount of the gift.

If the tax needed to fund the Pigou subsidy is raised from the rich, that all nets out to what we already do, i.e. grab tax off the rich in order to subsidise the poor. But if the tax is levied on the poor, they’re no better off.

Doubtless that argument of mine needs tidying up, but I suspect it’s basically valid: i.e. Pigou subsidies are pointless, so we might as well stick to what we already do, i.e. tax the rich and subsidise the poor.

Friday, 15 December 2017

Richard Murphy’s weak grasp of economics.

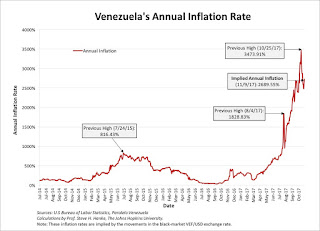

He advocates a rise in inflation to above the 2% target because that would help debtors*. As he puts it in reference to increased inflation: “….the country could do with some to assist those in debt manage the burdens they face.”

Well now there’s a teensy problem there, namely that creditors and savers are not complete idiots: that is, once they see that an increased percentage of what they save and lend will be eaten away by inflation, they’ll be reluctant to save and lend. Hey presto: interest rates are forced up, which is not exactly of “assistance” to “those in debt”.

Indeed, that’s exactly what seems to have happened for several years after the 1970s inflationary episode: that is, it took several years of low inflation to convince savers and creditors that inflation had in fact come down PERMANENTLY. Thus debtors were faced with several years of elevated interest rates.

Next, Murphy claims (2nd half of the para in which the above “assistance” point is made) that stagnant incomes are deplorable, and a way out of that is extra demand and inflation.

Well if inflation above the 2% target really does give us extra real GDP, why did no one think of that before? Put another way, the whole point of the 2% target is that economists think that while inflation above that rate clearly gives a faster rate of growth in GDP in nominal terms (i.e. in terms of £s, $s, etc), that is one big illusion. I.e. the consensus in economics is that once inflation rises much above the 2% target, the costs of inflation exceed the benefits. Or put another way, the consensus is that GDP growth is maximised when inflation is around the 2% level.

Of course that consensus might be wrong. It could be that GDP growth is actually maximised when inflation is 4%, 6% or some other figure. But those who want to make that claim need to set out some very detailed reasons to back that claim.

_________

* Article title: “On interest rates, growth and the need for the most massive rethink.”

Wednesday, 13 December 2017

What’s the optimum amount of national debt?

MMTers have solved this one. Others are still floundering, in particular Roger Farmer in this NIESR article on the subject, is all over the place far as I can see (1). So I’ll run thru this vexed question for the umpteenth time.

First (a point which Farmer does not seem to appreciate) there is little difference between national debt and base money, at low rates of interest, as Martin Wolf and Warren Mosler (founder of MMT) explained. I.e. both are state liabilities, or at least ostensible state liabilities. That’s why MMTers sometimes lump the two together and refer to the pair as “private sector net financial assets” (PSNFA).

Thus the first problem in answering the question “What’s the optimum amount of national debt” is that the very concept “national debt” is fuzzy: it has no clear boundaries.

Second, the amount the private sector spends is related to how much PSNFA it has (or if you like, how much “cash” it has). When people win a lottery, their weekly spending rises – a point which is common sense for most people, but a source of much confusion, difficulty and perplexity for some economists.

Ergo, the optimum amount of PSNFA is simply the amount that induces the private sector to spend at a rate that brings full employment. That’s not to say government should instantaneously adjust PSNFA every time there’s a recession. But what it can do is to simply print money and spend it, and/or cut taxes, and that will tend to raise PSNFA. So under that policy, PSNFA (or “the national debt” if you like) will always tend towards its optimum level, a policy advocated by Positive Money.

Interest on the debt.

Interest paid on the debt itself influences the “full employment equilibrium” level of that debt: that is, the higher the rate of interest paid on the debt, the more of it the private sector will be willing to hold, all else equal, as Warren Mosler pointed out.

A country which issues its own money can pay any rate of interest it likes on its debt, as MMTers have long pointed out. E.g. if a country thinks the rate is too high, it can reduce it by printing money and buying back debt, and then dealing with any excess inflation by raising taxes and “unprinting” the money collected.

So what’s the optimum rate of interest? Well Milton Friedman and Warran Mosler said “zero”: i.e. they said “don’t pay any interest at all”. And I must say I rather agree: certainly I don’t see any point in paying anything more than the rate of inflation, i.e. I don’t see a reason to pay a positive REAL (i.e. inflation adjusted) rate of interest. That’s for the following reasons.

First, the only really good reason to borrow is if you’re short of cash, and governments are NEVER short of cash: they can print the stuff, plus they can grab near limitless amounts from taxpayers. If a taxi driver wants a new taxi, and happens to have the cash to hand, he won’t borrow in order to buy the taxi. But then taxi drivers probably have more sense than economists.

Second, the old argument that government should borrow to fund infrastructure investment does not make sense because the ENTIRE education budget is an investment, so why don’t we fund that entirely via borrowing?

Third, I set out more argument against government paying any interest on its liabilities here (2).

So, to return to the original question, i.e. what’s the optimum amount of national debt or more properly, PSNFA? The answer is “whatever brings full employment”. And that very much ties up with Keynes’s dictum: “look after unemployment, and the budget looks after itself”. As to exactly what that amount of PSNFA will be as a percentage of GDP, that will depend on how thrifty or spendthrift citizens of the country are. The Japanese are relatively thrifty, thus their optimum PSNFA:GDP ratio will be on the high side. In other countries, the ratio will be lower.

________

Title of Farmer's article: "How much debt do we need? My answer: 70% of GDP".

Title of my article: "Government borrowing is near pointless".

Monday, 11 December 2017

The flaw in interest rate adjustments.

The common practice of adjusting interest rates so as to adjust stimulus makes no sense. Reason is thus.

It is widely agreed in economics that the optimum or “GDP maximising” price for anything (including the price of borrowed money) is the free market price, except where it can be shown that the free market is defective or where there is “market failure” to use the jargon. And in the case of the rate of interest, there is no obvious obstruction to the free market working: that is, savers shop around for the bank which offers the best (i.e. highest) rate of interest, and mortgagors shop around to find the bank which offers the best rate of interest from their point of view (i.e. the lowest rate).

The rate of interest is also influenced by the amount government borrows. Unfortunately there is no general agreement as to how much government should borrow. Milton Friedman and Warren Mosler argued that governments should borrow nothing, though Friedman thought there was a case for borrowing in war-time. I argued likewise here. (Title of article: "Government borrowing is near pointless".)

An alternative and popular idea is that government should borrow to fund infrastructure. But a flaw in that idea is that the entire education budget is investment of a sort. So should all education spending be funded via borrowing rather than via tax? There are no easy answers to that, though I argued here a few years ago that (in line with Friedman and Mosler thinking) government borrowing makes little sense.

So in the absence of any totally clear answer to the question as to how much government should borrow, let’s assume the optimum amount to borrow is X% of GDP.

Now let’s assume an economy requires stimulus. One way of imparting stimulus is to simply have the state print money and spend it, and/or cut taxes. And if you think that sounds outlandish, it’s actually not: having government borrow more with the central bank then printing money and buying back government issued bonds (“Gilts” in the UK) comes to the same thing as the above “print and spend” ploy. And the latter “borrow more and then buy back” is exactly what numerous governments have done since the 2007/8 crisis.

Note that that does not alter the above mentioned X%. At least there is no obvious reason why X should change simply because of some stimulus. I.e. a dose of stimulus will raise GDP by some percentage, but if for example there’s an argument for having government borrow to fund infrastructure and nothing else, then the total amount invested in infrastructure will presumably rise pari passu, more or less. Thus borrowing to fund infrastructure will remain at X%.

Interest rate adjustments.

A second way of imparting stimulus is to cut interest rates, and that’s done by having the central bank print money and buy up government bonds. But that reduces the amount of government borrowing to below X%. I.e. the total amount of government borrowing is then less than its optimum or “GDP maximising” level.

Provisional conclusion: stimulus should always be imparted essentially by having the state print money and spend it, and/or cut taxes.

What’s the economy for?

The latter conclusion ties up with a very common sense observation, namely that the basic purpose of the economy is to produce what people want, booth in terms of what they choose to buy out of their disposable income and in terms of the publically provided items (free education for kids etc) that people vote for at election time.

That is, given a need for stimulus (i.e. assuming the economy is working at less than capacity) the types of spending that need boosting on the basis of the latter “basic purpose” idea, is household spending and public spending. And households and the authorities responsible for public spending can, if they see fit, spend some of that extra money on extra interest to fund more borrowing.

But there is no obvious reason to assume that given a need for stimulus, that it’s JUST borrowing that needs to be boosted.

Friday, 8 December 2017

Friday, 1 December 2017

Higher bank capital ratios raise bank lending???

David Miles (economics prof at Imperial College, London) makes the odd claim in the Financial Times that raising bank capital ratios can result in banks lending MORE.

A large majority of those who have examined this question either think that raising capital ratios has no effect on bank lending or that the effect is to CUT lending. Those who back the “no effect” claim normally cite the Modigliani Miller theory, while those who claim that bank lending is cut normally claim that the MM theory is defective. Far as I can see, criticisms of MM are pretty feeble. I run thru them under the heading “Flawed criticisms of Modigliani Miller” here. So I conclude on that basis that raising bank capital ratios has no effect on bank lending.

However, the higher bank capital ratios are, the more difficult it is for commercial banks to create / print money. And as Milton Friedman among others explained, when the ratio is 100% (favoured by Friedman and others), then commercial banks, as Friedman explained, cannot create money at all. Plus the “right to print” pretty obviously amounts to a subsidy of commercial banks (as explained by Joseph Huber (p.31)). And cutting a subsidy for an industry contracts that industry. Thus I would claim that raising capital ratios will in fact cut lending.

However, given the enormous expansion of lending and debt in recent years, that is hardly a big problem. Plus the deflationary effect of less lending is very easily countered via conventional stimulus, fiscal and/or monetary.

Thursday, 30 November 2017

Increase public investments when interest rates are low?

A popular belief among the great and the good is that since governments can borrow at around a zero real rate of interest, governments should borrow more to fund public investments like infrastructure. E.g. this Oxford economics prof says “The obvious response is for the government to borrow to increase public investment, particularly when it is so cheap to do so.”

Unfortunately there’s a problem with that argument which is that the only reason governments can borrow at ultra-low rates of interest is that governments have coercive powers: they can confiscate money from taxpayers with which to repay their creditors even when their investment projects are a flop.

Thus the rate of interest that should be charged to public investments is the sort of rate that a private infrastructure provider would have to pay, and that is significantly more than the approximately zero real rate of interest that many governments pay.

The original funders of the English-French channel tunnel lost nearly all their money. So what rate of interest would you want for funding a similar project in the future?

Sunday, 26 November 2017

24 economists support Old Mac Donald.

24 economists have produced a statement in support of John McDonnell, the shadow finance minister (aka “Chancellor”). I’ve reproduced their letter below, followed by my less than entirely flattering response. Their statement reads:

Andrew Neil of the BBC Politics programme recently challenged the Shadow Chancellor, John McDonnell, on the likely cost in interest payments of additional public borrowing. He suggested that current debt interest payments are estimated at £49 billion, and rising. His use of £49 billion was misleading, as it included £9bn owed by the Treasury to the Bank of England (BoE). Because the Bank is part of the public sector, £9bn is in effect owed by government to itself, as the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) explains.[1] The government’s debt interest payments are therefore £40bn.

But the £40 billion is not meaningful in isolation. It is best understood as a share of the UK’s national income or GDP. This amounts to just 2% of GDP – a historically low share of the national ‘cake’. This is remarkably low, given the costs (debt) incurred by the government to bail out the private financial system after the 2007-9 global financial crisis, and given Britain’s falling wages which reduce government tax revenues. Above all, given the slowest economic recovery on record.

In 1987/88 when Conservative Chancellor Nigel Lawson was stoking an unsustainable boom, debt interest (see the OBR’s databank on public finances here) was at virtually the same level as the OBR estimates it is today - circa £40 billion (in 2016/17 constant prices). When the Tories left office in 1996/7 debt interest payments were again at the same level as estimated today – £40 billion (also in 2016/17 constant prices).

But there is a stark difference between the period of Lawson’s boom, the Conservative government of 1996/ 1997 and Britain in 2017. Today the nation is struggling to recover from the devastating effects of a global financial crisis, and for ten years has suffered falling wages and incomes, the dismantling and defunding of vital public services and with it, the loss of the’ social wage’. And thanks to austerity, this has been the slowest economic recovery from a slump in history.

Chancellor Nigel Lawson and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher were relaxed about spending close to £40bn on debt interest payments at a time of prosperity. Today we face ongoing economic weakness, the rise of populism and the possibility of a major economic shock posed by Brexit in 2019. In these circumstances, neither Labour (nor indeed the current government) should be deterred from borrowing for productive investment, especially at a time when interest rates are historically very low.[2]

Increased public investment in productive activity will expand our nation’s income and with it, government tax revenues. By so doing public investment will enlarge the economic ‘cake’ and help bring down future debt interest payments as a share of GDP.

My response.

First, the fact that the cost of Mac Donald’s proposals are small compared to the cost of an almighty blunder, i.e. the 2007/8 bank crisis, is not a brilliant argument for those proposals.

Second, the fact that we’ve had the “slowest economic recovery on record” (just like other countries) is not an argument for a large dose of stimulus NOW. The crucial determinant of whether stimulus is justified NOW is what inflation is doing NOW. And in the opinion of the committee charged with looking at that question, the BoE MPC, inflation is sufficiently uppity NOW, that stimulus needs reining in.

Of course the BoE might be wrong, but determining whether IT IS WRONG requires a detailed look at how much inflation is cost push and how much is demand pull, rather than vague statements about the “slowest economic recovery on record”.

Third, this passage is defective:

“In these circumstances, neither Labour (nor indeed the current government) should be deterred from borrowing for productive investment…”. Total confusion of unrelated issues.

Assuming public investment is best funded via borrowing (and that is very debatable for reasons spelled out by Milton Friedman and Warren Mosler), the optimum amount of such borrowing will not be much affected by whether the economy is at capacity or in recession. I.e. sensible investment decisions are taken on the basis that the economy is at an average sort of level, capacity wise. I.e. the argument that “stimulus is needed, so let’s have a big increase in investment spending” makes little sense.

Moreover, sudden changes in investment spending, or any other form of spending, tend to make for inefficiency. Put another way, when stimulus is needed, there is merit in spreading the extra spending as widely as possible over public and/or private sectors.

Friday, 24 November 2017

Minsky’s absurd objections to full reserve banking.

Jan Kregel wrote an article on Minsky’s views on full reserve banking entitled “Minsky and the narrow banking proposal..” (Public Policy Brief, No.125, published by the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College). “Narrow banking” as defined by Minsky is the same as what is normally called “full reserve banking”.

I actually tackled this article of Kregel’s five years ago in 2012, and set out some flaws in it. However, on re-reading Kregel’s article, it struck me there are even more flaws to be exposed. This present article runs thru some of the flaws I set out in 2012 and in addition deals with two or three new ones.

The first objection to full reserve cited by Kregel is one not actually raised by Minsky, but rather by Neil Wallace, whose objection is that full reserve “eliminates the banking system” (p.5, 2nd column).

Well the answer to that is that advocates of full reserve are well aware that full reserve is such a fundamental change to the bank system that it is perfectly fair to describe that change is “eliminating the banking system” as we know it.

Indeed Matthew Klein penned an article, published by Bloomberg, in support of full reserve entitled “The Best Way to Save Banking is to Kill It”.

You could say the internal combustion engine is inherent to the definition of the word “car”, and thus that banning internal combustion engines and replacing them with electric motors and batteries equals the end of the motor car. That, however, is just semantics. The important question is whether fundamental changes to banking or cars make sense.

Stability.

The next objection to full reserve cited by Kregel and made by Minsky is: “such a system could neither ensure the stability of the real economy nor assure stability of the capital financing institutions…”. The answer to that is as follows.

The advocates of full reserve never claimed that full reserve would actually bring the above “stability”. For example a work by Positive Money and co-authors which advocates full reserve and is entitled “Towards a Twenty-first Century Banking and Monetary System” specifically says that demand management under full reserve is needed just as under the existing system.

Moreover, the implication in the above “stability” quote from Kregel’s article that the EXISTING bank system brings stability is hilarious. As readers may have noticed, we had a major bank crisis in 2007/8 which gave rise to a ten year long recession.

Return on investments.

The above “stability” quote from Kregel’s article continues as follows.

“First, the real investments chosen could still fail to produce the anticipated rate of return; and second, sectoral over-investment and financial bubbles could still exist if there were herding behavior by the investment advisers of the trusts that produced pro-cyclical financing behavior. There would always be a risk of investors calling on the government to save them from financial ruin.”

First, as regards “investments” which “fail to produce the anticipated rate of return”, that’s hardly unusual under the EXISTING system!!!! Ford’s disastrous Edsel car did not cause the sky to fall in.

As regards the idea that investors might “call on government to save them from financial ruin”, investors under the existing system do not normally go running to government for help when faced with ruin, and they normally get short shrift when they do. There is no general expectation that government comes to the rescue when there’s a stock market crash. Exactly the same would apply under full reserve.

Of course there are well known cases of where governments HAVE STEPPED IN under the existing system: e.g. General Motors and Chrysler were given government assistance in 2008. And then there were the trillions loaned to banks at sweetheart rates of interest during the recent crisis. Thus the charge by defenders of the existing bank system that under full reserve there’d be instances of taxpayer funded assistance is a joke: the words pot, kettle and black spring to mind.

Demand management.

The next objection to full reserve has to do with demand management, and is in effect just a repetition of the above mentioned demand management objection. Kregel says “In such a system it is evident that total private saving would exceed investment by the private sector’s holdings of narrow bank deposits and government currency, creating a tendency toward deflation or recession.”

Well the quick answer to that is that, as already pointed out, advocates of full reserve are well aware that demand management is still needed under full reserve.

Large government sector needed?

Next, Kregel says “In the absence of a large government sector to support incomes, liabilities used to finance investment could not be validated in a narrow bank holding company structure.”

I’ve no idea what that’s supposed to mean. But the claim that a “large government sector” is needed is nonsense. What IS NEEDED as already pointed out, is demand management, i.e. deficits (and maybe the occasional surplus). But deficits are easily arranged even given a government sector half the present size.

To illustrate, public spending as a percentage of GDP in the US is near 40%. If that were halved, that would mean a deficit equal to about 20% of GDP would be no problem at all: that could be done by government ceasing to collect any tax and continuing to spend at a rate that equalled 20% of GDP. And of course a deficit equal to 20% of GDP is truly massive: it’s unheard of, thus the “large government sector” alleged problem mentioned above is nonsense.

Innovation.

Next, Kregel says, “But, even more important, it would be impossible in such a system for banks to act as the handmaiden to innovation and creative destruction by providing entrepreneurs the purchasing power necessary for them to appropriate the assets required for their innovative investments. In the absence of private sector “ liquidity” creation, the central bank would have to provide financing for private sector investment trust liabilities, or a government development bank could finance innovation through the issue of debt monetized by the central bank.”

Frankly this is getting more absurd with each succeeding paragraph. It is also not entirely clear whether the latter objection to full reserve is Minsky’s or Kregel’s.

At any rate, as Kregel himself explains earlier in his article, under full reserve, all funds supplied to non-bank corporations come effectively via equity and bonds rather than via bank loans which themselves are funded via deposits. Thus the idea that under full reserve, non-bank corporations and firms have no way of obtaining “purchasing power” is pure, unadulterated nonsense. They just get their purchasing power in a slightly different way.

Indeed, some corporations under the EXISTING SYSTEM choose to fund themselves mainly via equity rather than bank loans: for example Google is funded 90% by equity, and Google is hardly a failure when it comes to “innovative investments”.

Conclusion.

Minsky and Kregel’s criticisms of narrow / full reserve banking are hopeless.

Thursday, 23 November 2017

The bizarre failure of productivity to improve in construction.

In the last 20 years, productivity in Germany and Japan has not risen at all. In France and Italy it’s fallen by one sixth. And in the US it’s halved since the late 1960s. That’s according to this Economist article. Absolutely hopeless.!!!!

According to the Economist, the industry has become LESS capital intensive because builders are put off investing by boom and bust. It has also failed to consolidate. Another significant problem is different building codes in different parts of the same country.

However, we had boom and bust 50 years ago, and presumably also different building codes in different parts of the same country. So neither of those strike me as good explanations.

The Economist rightly considers mass production pre-fab as a possible solution. Strikes me that will never really get off the ground in a big way absent very very large scale mass production of apartment units.

The head of one of the UK’s largest construction firms said a few decades ago at a House of Commons investigation into this that the scale of investment needed to really reap the benefits of mass produced apartment units would require more money than an individual firm could come up with. Unfortunately I forget his name or the firm he worked for.

Possibly this is an area where Mariana Mazzucato’s ideas on entrepreneurial governments might work. For all the tens of thousands of words she writes, she seems a bit short of actual examples of where the entrepreneurial state idea would pay dividends.

On the other hand, it may be that productivity improvements are just not possible at the moment. After all, the typical house is constructed much the same way as in Roman times: one brick or stone plonked on top of another with mortar in between, plus wooden floor joists and wooden floor boards, plus tiles on the roof.

Wednesday, 22 November 2017

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)